Fines and Fees Justice Center Advisory Board Member, Alexes Harris, and New York State Director, Katie Adamides discuss how fines and fees have become a “toxic revenue source” throughout New York state. Harris notes ending predatory court fines and fees such as the mandatory surcharge can “send a great message to other states” and help pave the way towards national reform.

Read the full text of the article on Law 360 here.

***

NY Push To Nix Court Fines, Fees Could Spread Nationwide

A new push to eliminate court fees and fines in New York could spur similar criminal justice reforms in other states, according to experts and advocates across the country.

Legislation proposed by New York state lawmakers last week would eliminate court fees, mandatory minimum fines, garnishment of commissary accounts and incarceration on the basis of unpaid fines and fees.

The so-called End Predatory Court Fees Act is meant to help curtail New York’s reliance on fines and fees as a revenue source while the state grapples with a $14.5 billion deficit fueled by the coronavirus pandemic and thousands struggle to pay for food, housing and other basic necessitates.

“This is a key moment — a lot of people are fearful that local jurisdictions are going to turn to more fines and fees,” said Alexes Harris, a sociology professor at the University of Washington who wrote a book, “A Pound of Flesh,” on court-ordered monetary sanctions.

“Doing this in New York would send a great message to other states,” Harris added. “It would be tremendous.”

Like other jurisdictions, New York state currently imposes automatic court fees for every conviction and traffic ticket: $95 for violations, $175 for misdemeanors and $300 for felonies.

But the practice has faced increased scrutiny in the wake of a U.S. Department of Justice investigation following the police shooting of an unarmed Black teenager, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri. A federal investigation concluded that police there disproportionately targeted Black people for traffic stops, citations and arrests to get criminal fees to fill city coffers, collecting over 23% of its revenue from fines and fees in 2015.

Six percent of all U.S. adults are struggling with court debt from fines and fees, according to a report released in May by the Federal Reserve Board. Just 5% of white families reported unpaid legal expenses, fines or court costs compared to 12% of Black families and 9% of Hispanic families.

“Nationwide, the use of court-imposed fees in the criminal justice system, even against indigent defendants, has worked, often, to criminalize poverty itself,” said Gene R. Nichol, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law who co-wrote a 2017 report on the practice in the state.

“It is great to see New York taking the matter seriously,” Nichol said. “Other state legislatures should as well. We supposedly outlawed debtor prisons many decades ago.”

The proposed legislation, from Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou, D-Manhattan, and state Sen. Julia Salazar, D-Brooklyn, is drafted but has yet to be officially introduced. A spokesman said Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office will review the proposal.

Another preexisting bill, from state Sen. Luis Sepulveda, D-Bronx, Assemblywoman Carmen de la Rosa, D-Manhattan, is being reworked and would eliminate parole and probation fees.

A few localities have already implemented similar reforms. In California, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted in February to eliminate all criminal administrative fees, after similar measures were approved in other state counties including San Francisco. Iowa eliminated and reduced some court fees and fines this summer, but increased others.

And some states and cities, like Maine and Chicago, halted the collection of these fees during the pandemic.

“The dominos are starting to fall on criminal debt in this country and New York is not just any other state — it will set a national example,” said Brandon Garrett, a Duke University Law professor who co-authored a recent study on courts’ use of fines and fees. “New York is also representative, unfortunately, of the widespread criminal harm that debt can cause.”

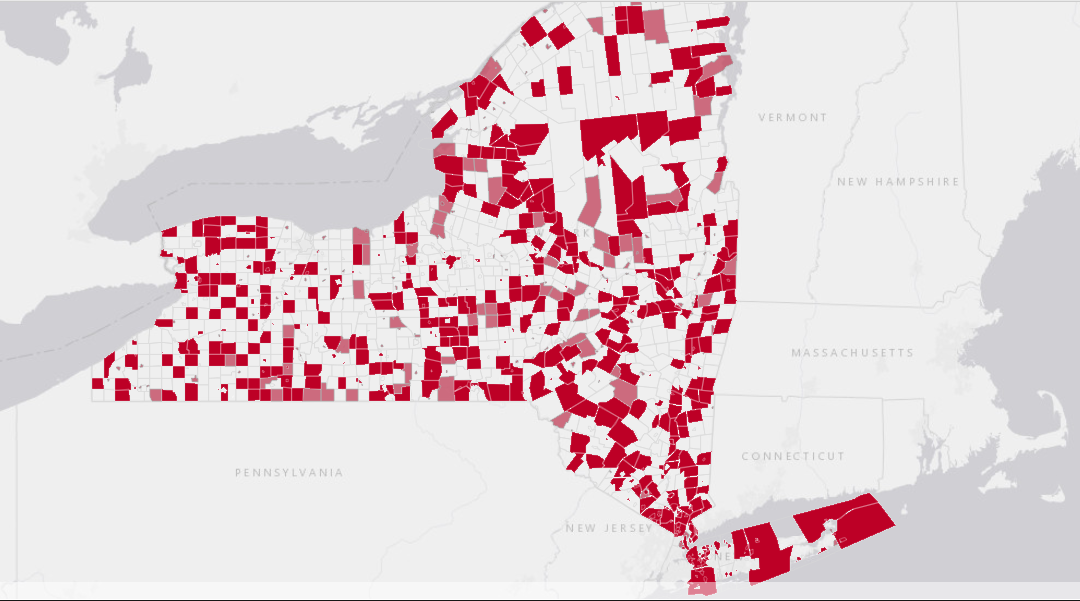

Thirty-four New York localities were found to be just as reliant as Ferguson on fines and fees, according to a report released this week by the Fines and Fees Justice Center’s No Price on Justice campaign.

“It’s toxic revenue,” said Katie Adamides, the New York state director for the center. “We should never rely on someone breaking the law for the government to break even.”

The New York Legislature already passed a bill this summer that, if approved, would forbid the court from suspending someone’s driver’s license for failure to pay fines imposed for conviction of certain traffic violations or failure to appear, as well as require the offer of a payment installment plan for fines or fees.

Right now, failure to pay court fines in New York can lead to more prison time or a bench warrant and they are often coupled with additional penalties, like a $25 “crime victim assistance fee” or a $50 “DNA databank fee.” While New York judges used to be able to waive mandatory surcharges for low-income defendants, a 1995 crime bill removed that judicial discretion and made these fines mandatory.

New York has also repeatedly increased the fees, which were as low as $15 for a violation and $75 for a conviction when they were first established in 1982.

The New York City Bar Association urged state lawmakers to end criminal court fees in 2018, calling them a “regressive tax” on people who are also the least able to pay.

But the economic fallout from COVID-19 has only intensified the need for reform, experts and advocates say, with low-income people of color facing the most death and job loss during the pandemic.

“The same folks who are suffering disproportionately with coronavirus are the ones that disproportionally pay or are charged fines and fees they cannot afford,” Adamides said.

Though cities and states like New York are struggling to recoup revenue lost as a result of the pandemic, it’s unclear whether court fines and fees would actually help close the deficit.

Last year, New York City’s criminal courts imposed more than $10 million in surcharges but only collected $3 million, according to the report from the No Price on Justice campaign. The city’s Supreme Courts imposed some $4 million but only collected about $611,000, the report states.

Creating a system to enforce fines and issue bench warrants when they go unpaid also costs governments millions. And enforcing court fines and fees increases the number of traffic stops and other police encounters that low-income people of color experience, Harris said.

“It creates the scenarios that can lead to the killing of Black people in this country,” said Harris, who also serves on an advisory board at the Fines and Fees Justice Center.

Recent Comments